A New Way to Web

Imagine that you’re trying to sell a car.

It’s in good condition, but you can’t really prove that. So buyers assume that it’s a lemon. They aren’t willing to pay you what it’s worth, which means you don’t have any incentive to sell. And so you don’t — and neither do the other honest people looking to sell their “plums”. Now, the only used cars on the market really are lemons. This is a concept called a Market for Lemons.

That’s what Lars Doucet predicted would happen to the internet after the launch of OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Doucet was focused on what would happen when you can’t trust that the person behind the screen is a human, but the Lemonization of our online spaces — the decline in trust and quality — seems to be breaking the internet as we know it entirely.

The tools that we’ve gotten used to leveraging in our businesses, like artificial intelligence and social media algorithms, along with other business owners in our network, are all drowning us in a sea of noise.

It’s leading to what feels like a complete devaluation of what it means to have a voice in the growing cacophony of louder and louder voices.

And the online business space has to catch up.

What happened to the internet?

To understand the nature and scale of what’s happening to the web, it’s helpful to understand the Dark Forest Theory.

At night, a forest might look devoid of life. There is no movement, no noise. But, of course, the forest isn’t empty; the animals are just protecting themselves from the predators that come out at night.

We see this online, too. So much of the web is full of advertisers, trackers, spammers, clickbait, bots, and trolls. In response, people often retreat into private spaces like Facebook groups, Slack workspaces, and group chats.

When we stare into the Dark Forest of the Internet, it seems completely overrun by predators. The rest of us are still here, we’re just hiding.

As people who work online, it’s harder for us to stay out of the Dark Forest; we often rely on ads, algorithms, and tracking for our work. It feels like we can’t entirely retreat into safer spaces because we might lose the visibility we rely on for sales.

This is a problem. The Dark Forest is expanding.

As Maggie Appleton wrote about the rise of Large Language Models like ChatGPT:

We're about to drown in a sea of pedestrian takes. An explosion of noise that will drown out any signal. Goodbye to finding original human insights or authentic connections under that pile of cruft.

If you thought bro-marketers and get-rich-quick gurus were a blight on online business before, they can now generate effectively limitless amounts of content with nearly zero barrier to scale. If you’re tired of spam pages popping up in your search results, entire sites can be generated cheaply and can post hundreds of articles a day. If you’re already annoyed by bots, dozens of them can be spun up at once, each with their own unique post history, personality, and dynamic responses.

The Dark Forest is no longer bottlenecked by manpower.

Meanwhile, the very fabric of first generation social media seems to be breaking down. Spaces that used to foster connection and convenience have become “too much echo chamber… too much viewing people you know in real life as marketing categories,” according to one person quoted in a recent Wired article.

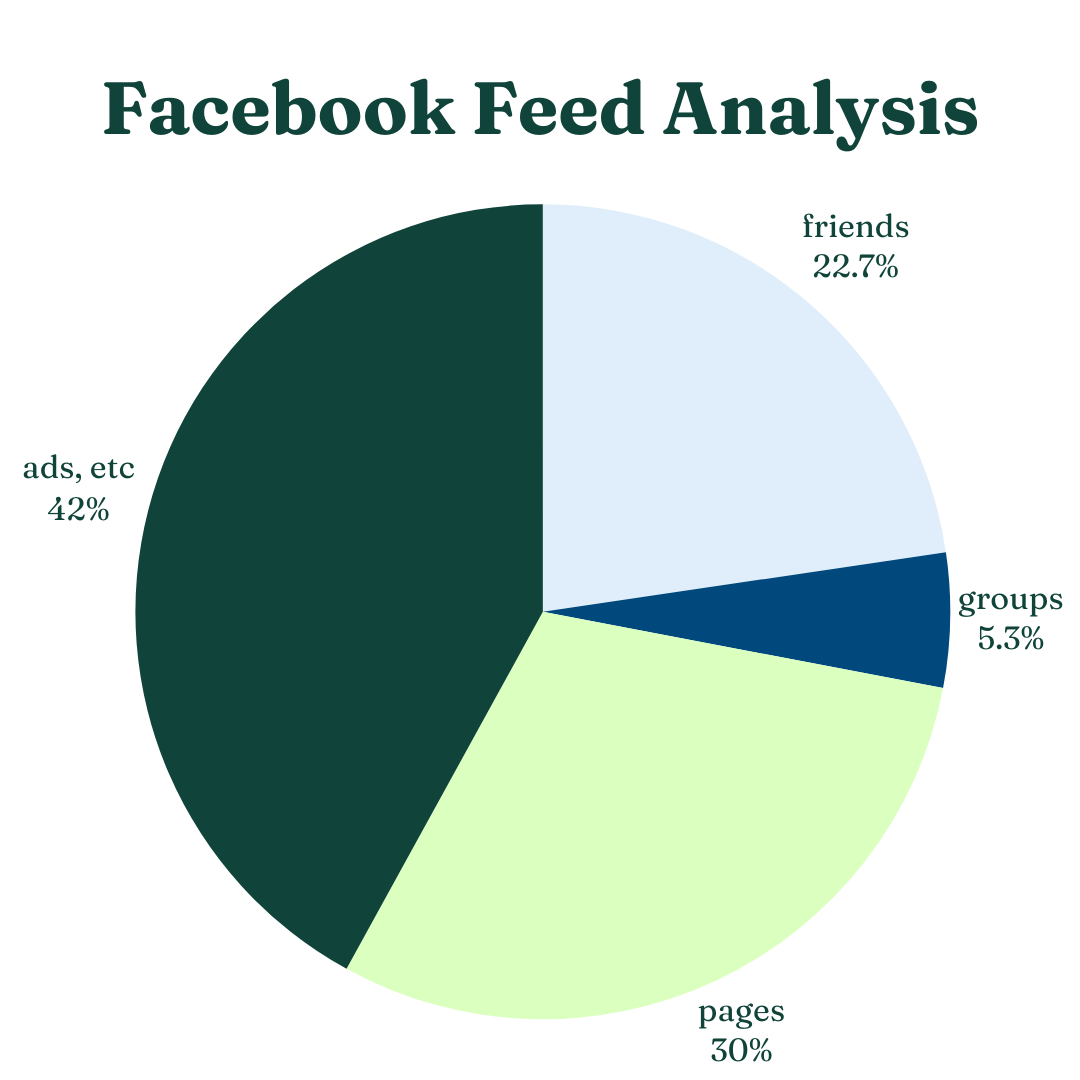

To figure out whether things are as bad as they feel, I did an analysis of my social media feeds across Meta's Facebook, Instagram, and Threads.

On Facebook, approximately 22.66% of posts were from my friends, 30% were from groups I’m a member of, 5.33% were from pages I follow, and a whopping 41.99% of posts were sponsored or suggested — meaning nearly half of my feed is made up of content I have not opted into seeing.

Threads is a hellscape of meta-posting. 59% of posts in my feed are follow-trains straight out of 2014, with the majority of users calling on the All Powerful Algorithm to send “the girlies” their way. Only 41% of posts were people sharing something that didn’t have to do with Threads itself — although even some of those posts were just about Twitter or other social media platforms.

Instagram was marginally better, with 68% of posts being from accounts I follow and 32% being sponsored or suggested content. Although it didn’t feel much better than Facebook, considering the sheer disorganization of the feed timeline.

None of this even takes into account how things like moderation have failed across the internet, even on platforms that somehow carry legitimate geopolitical weight.

We cannot rely on platforms that continue to decay.

Still, it might not seem all that bad to the users who are the ones advertising. Perhaps you don’t mind if nearly half the posts in your feed are advertisements if you’re benefiting from the placements of those ads.

But don’t let them fool you.

Another helpful concept here is Cory Doctorow’s theory of enshittification or, more G-rated, platform decay.

This refers to the lifecycle of online platforms:

[F]irst, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back the value for themselves. Then, they die.

Facebook, Doctorow writes, is “terminally enshittified”, having started as a platform that put you in the same digital room as your friends and family; once we all fully bought into the FOMO of Facebook, they showed us less from our friends and more from pages and companies we never subscribed to; once those companies relied on Facebook for traffic, they started suppressing posts that were “boosted” (i.e, paid for); now, nearly half of our feeds are clogged with content we didn’t ask for.

More than ever, social media is bad for the consumer and bad for the businesses that have built over-reliance on their algorithms.

So: What are we going to do about it?

Three New Ways of Working Online

This is difficult, first because of how siloed we are. It’s harder for us to find and connect with industry peers when, for so many of us, our work is highly individualized and remote. It’s also hard because most of us aren’t programmers or developers; we lack the language, context, and skills to truly contribute to what the next era of the web looks like.

But we rely on this technology for our livelihoods. We aren’t casual internet consumers, and being passive through these shifts put us, our businesses, and our audiences at risk.

If we don’t get involved, the very people we fight to stand out against will be the ones terraforming this new Wild West.

For that reason, I’m exploring three specific changes to the way I think about online business. These are experiments that I hope you’ll consider joining in on.

Free Information

I believe that we should be sharing freely.

This doesn’t mean that we should feel obligated to write a dissertation for every comment we get, or that we shouldn't protect our intellectual property. But I don’t think we should be bookending advice with calls-to-action.

Instead, what I will personally focus on charging for is troubleshooting, roadmapping, and implementation.

Here’s how I’m personally thinking about this:

Imagine someone asks how to create filtering rules in their email inbox. If I have the time, I can write a brief tutorial or link to a relevant guide — that’s free information.

But if that same person comes back and says, “I think I set up the rule incorrectly, because some emails are being deleted,“ that’s an action-based problem. If they were to ask me to log into their inbox to find the issue (troubleshooting), explain how to fix this specific mistake (roadmapping), or to actually fix it myself (implementation), any or all of those tasks could make up a billable project.

I don’t see this being a hard-and-fast rule, but more of a guideline. To me, it’s essentially the idea that if I had to Google something to find out how it works, then it’s not something I should be charging for; it’s likely more beneficial for everyone that I point them to processes and resources that I know to be correct, rather than let someone flounder in the sea of spam and disinfo. However, if it’s something I created, transformed, or did myself, an expectation of compensation is reasonable.

Plenty of business owners do this already, so adopting a more intentional approach to it won’t be too big of a change for most of us.

Atomic Solutions

The second principle is all about atomicity, which I originally thought about after researching how to take more effective notes.

“Atomic notes” are notes that focus on a single idea or concept. Instead of having, for example, one large document that holds all of your notes on marketing strategies, each strategy would have its own note, allowing you to link different ideas from each strategy together. This process, that of proactively combining multiple smaller ideas, can lead to bigger, more interesting ideas of your own (AKA, idea sex).

I think we can take a page from this book.

Many of us have been encouraged for years to define our signature offer, develop our signature framework, create our signature course. How much are our signature processes helping our customers? How can we tell that it works for them? How ethical is it for us to sell products for which we can’t measure results?

Sure, you can’t guarantee your customers and clients a specific outcome, but surely there must be a middle ground?

That would allow us the flexibility to follow our creativity and the meandering interests so many of us have and it would allow our audience to use our building blocks to create the life, business, or outcome that they’re looking for.

Take Leonie Dawson for example. One of her products teaches you how to create and sell a course in 40 days; another teaches you how to get organized in 21 days; another teaches you how to hire a VA. These are all atomic solutions that solve a single problem and offer a single outcome: you know the offers work because you’ve created a course, gotten organized, or hired a virtual assistant. Leonie doesn’t need to guarantee any of those outcomes; just by nature of focusing on one thing, there’s a built-in rubric against which buyers can measure their work. And, if someone does want to sell a course, declutter their house, and hire an assistant, Leonie occasionally offers a convenient “everything offer”, giving customers the best of both worlds.

Essentially, I think massive four- and five-figure products are on their way out, and quickly. People are tired of being sold to, they’re tired of being influenced, and I think they’re growing tired of all the courses and templates that promise they can do it all.

By focusing on atomicity, we can truly get out of the habit of trying to create one-size-fits-all solutions, which most of us know are rarely as effective as they sound.

Cozy Web

The Cozy Web is the principle I’m most excited about exploring; this is where we ditch algorithms and embrace real community.

These are spaces that are meant to keep us safe and shelter us from the Dark Forest.

Unfortunately, there is a downside: like any gated community, the cozy web is not accessible to everyone. You have to know that these spaces exist, which not everyone does, and you have to know how to get into them — usually by knowing someone who’s already on the “inside”. It is a privilege to be able to find safe spaces online.

How can we create communities where we and our audiences are protected, but where those who need us don’t get lost and aren’t held up at the security booth?

I’m still working out what this looks like in practical terms, but I have some ideas. Truthfully, I think we need to bring back the webring.

If you’re not familiar, a webring is a collection of websites that contain a similar theme. They were especially popular on the early-internet, but they do still (kind of) exist today.

Let’s say you built a website all about your Himalayan cat, and you come across a similar website from someone who writes about their Siamese cat. Maybe you notice that the Siamese cat website has a button on it for the “Cat Culture” webring (which is not a real webring, but should be). You could click that link to see all the other sites that have joined Cat Culture; some of those sites might be in even more webrings, leading you to even more websites you might be interested in. You could even join the Cat Culture webring yourself, add the button to your site, and instantly become part of a larger online community that helps you connect with others and get your website seen.

What might this look like today, especially when you run an online business instead of a personal blog?

Picture this with me:

Sarah is productivity coach who writes a lot about time management and productivity from the lens of someone with an invisible disability. Despite the fact that she’s learned to live with her condition, she still often finds it alienating; she struggles to do more, like networking or building relationships online, after a long day of work.

One day, Sarah starts thinking about taking a vacation to get some needed deep rest. She finds a travel blogger with a button on her homepage: Invisible Disability Community. Amazed, she clicks the button and finds herself on a new website, full of links to other pages run by people in a similar position to hers.

On this website, maybe she can view all of the content that’s been published by the members of this webring. Maybe she can view everything the webring members have for sale. Maybe she can join a Discord server or a Facebook group that holds space specifically for others struggling with chronic conditions.

Sarah can join the webring for free and add the button to her website, helping anyone who finds her business find other resources and communities that might be helpful for them.

And maybe Sarah doesn’t stop there; maybe she finds webrings for other things that are important to her, like those focused on social justice or those built specifically for coaches.

I imagine this as a type of expanded cozy web, where there are protective measures in place for existing members, but where the barrier-to-entry is low enough that these spaces are easy to find, join, and participate in. A truly grounded and intentional space rather than traditional networking groups or course communities. A space that lets us lean into the humanity and creativity of our businesses.

How could we change the way business, marketing, and community work online if we took this kind of decentralized, but connected, approach?

Whatever We Do, We Do it Together

Those three principles are the tangible steps I plan to start making today to participate in the changing landscape of the web, rather than being a passive observer.

If I’ve convinced you — if you want to talk more about free information, atomic solutions, or building our own cozy web — I hope you make your voice heard with me. If I didn’t, that’s okay; it wouldn’t be fun if we all did the same stuff anyway.

Member discussion