Earnest on Main: Rethinking the Performance of Authenticity Online

Back in April, a woman named Lindsay Jean Thomson came across my TikTok feed and used a phrase that has made its way into my regular vernacular:

“Sorry for being earnest.”

She was responding to a question about how to be an advocate for your artwork without feeling “too proud”.

You’re not too proud. I actually want you to be more proud. You made something with your hands, with your heart. And I’m sorry for being earnest, but, like, that’s an act of optimism, of bravery, of love.

It made me laugh, because I also constantly feel the need to apologize for being sincere online. It almost feels confrontational. Exhibitionistic. It asks the reader or viewer or user to really contemplate what you’re saying — to be active in the process of consuming your content.

It doesn’t follow the rules about how much you or your audience are supposed to care.

The specific expectations change depending on the platform, area of the internet, and why you’re there, but the messages are largely the same across the web: Grow an audience, but don’t worry about vanity metrics. Tell your story, but only when it’s palatable for mass consumption. Engage with content, but only as a means to your own end; you need to be a creator, not a — 🤢 — consumer.

Don’t care about numbers, context, or the conversations happening around you.

And yet, despite all of these ““best practices”” for existing and (especially) working online, one of the most common pieces of advice you’ll hear is to be “authentic”.

Be yourself, but only within the framework we’ve already established, and also don’t get too excited or take it too seriously or get too invested — it’s just the internet.

This was a primary sticking point behind starting this newsletter in the first place. I think we all crave authenticity; we want to share our real selves in our work, and we appreciate seeing the humanity in others beyond polished and perfected content marketing funnels. We want to see others and be seen ourselves. We want to engage in meaningful dialogue. We want to feel safe sharing more deeply about who we are.

But the more I explore what that looks like, and the more I compare it to concepts that feel a bit more concrete (like earnestness), the more my thought process is shifting.

My honest conclusion? Authenticity online is a joke.

It doesn’t really mean anything. It’s a nebulous idea that allows some people to feel like they’re Doing The Internet better than others. It’s a vibe check. A reaction you have to someone else. It’s not a real thing.

Authenticity is an unrealistic expectation in digital spaces.

The most relevant definition of “authenticity” for our purposes refers to being “true to one’s own personality, spirit, or character”. To be authentic online, then, is for your digital persona to match your offline persona — for what you share publicly to be a genuine reflection of what you are experiencing, feeling, and being in private.

This doesn’t work.

To “be” offline doesn’t require anything from you. You exist without any discernible effort. I think therefore I am, etc.

The internet is different. It requires us to write ourselves into being. We don’t exist online without articulating who and what we are. We have to act to be tangible in the digital world.

In other words: Being online inherently requires you to curate a persona. There is no way to be online the way you are IRL — not really.

This comes from danah boyd (intentional formatting), a researcher with an extensive background in social media scholarship. She talks about this idea of articulating identity online in a chapter she wrote about the early social networking platform Friendster; it was a challenge for early social media users because, for the first time, they had to think about what to formalize and broadcast about themselves in this limited environment.

And how you build your digital persona(s) is further complicated by the very function social media serves: decontextualization.

Social “context” shapes how we perform identity — how we convey who we are to others. The more information (or data) we have about a social environment, the people in it, the expectations around it, the easier we can navigate it.

Think about attending a professional conference. If you walked into a giant event without any information about the agenda, key speakers, or the primary topics and themes, you’d probably feel like a deer in headlights. You wouldn’t know where to go, who else is there, what they care about or how to talk to them.

But if you walked in knowing all of that — what’s happening when, who’s talking about what — you’d have a much easier time navigating and taking advantage of the experience.

You can enjoy and participate in the conference in either scenario, but the more context you have to work with, the more you can adjust your behavior to suit your goal for attending.

While that might not sound “authentic”, adjusting your performance to your audience is a legitimate social tool that enhances your ability to connect, communicate, and engage appropriately in a given setting.

Social media takes a lot of this context discernment away.

We curate personas that best match the platform we’re on, we agonize over the parts of ourselves that we want to make public, and it’s impossible to recreate the complexities of ourselves in a pre-established format. As a result, we get lost in these siloed, concocted performances of ourselves that are divorced from the rich data that makes us who we are.

But that’s not all social media does.

Social media collapses everything.

Sticking with the theme of context for a second, let’s chat about another one of danah’s concepts: context collapse.

Context collapse refers to the “flattening of multiple audiences into a single context” (source), like how social media brings together disparate groups of your friends, family, and colleagues into the single context of one online profile.

Social media does not model our IRL social networks. It flattens our social networks by applying the same type of access, importance, and labels to varying types of relationships. This has become a little more flexible since danah started writing about it (e.g, by limiting who can view or comment on posts), but we’re ultimately required to use the same identity performance across multiple groups at once.

We don’t do this in real life. My work persona is different from my family persona which is different from my persona with friends. Flattening takes away that agency and requires us to present one persona in all areas of our lives — or to limit access to this persona in a way that can have social consequences. How might your relationship change, for example, if you decline a client’s Facebook friend request?

Another consequence of context collapse is how information spreads. An innocuous post meant for your followers can be seen by thousands or millions of people who don’t “get it” — who don’t have a frame of reference for the broader context of what you mean, which, because the internet is what it is, can lead to poor-faith engagement at best and harassment (etc) at worst.

An artist acquaintance of mine went viral a few years ago after posting that he was doing a performance piece that effectively involved doing nothing. Those of us who know him and are familiar with his art were very much in on the joke; those who do not know him couldn’t call him an idiot fast enough.

He didn’t care too much about how the internet ran with his art piece, but what if it isn’t a cheeky performance that people are ridiculing you for?

This is a legitimate concern when all barriers between contexts are removed.

Time Collapse

This is an expansion on context collapse that says social media also blurs the lines between past and present, which makes it even more difficult to manage our online performance. We are always changing, but social media collapses our identities and performances across time into a nonlinear “lifelog” of posts.

This collapse is characterized by three things:

- Using full names, which attaches your digital footprint to your offline identity.

- Content archives, which make it possible for old digital traces of identity to resurface and “disrupt” how we currently see ourselves or perform ourselves online.

- Archives being searchable by others, which can lead to stricter self-management, preventing us from even getting close to that elusive idea of “authenticity”.

This is a really interesting idea to me, in part because I’ve always appreciated the way our digital “selves” interact with time. I love that I have archives on- and offline that let me travel back to hard moments, good moments, bad haircuts, nostalgic music, old friendships, vague-posts about whatever drama I was going through at the time.

But the longer we’re online — individually and culturally — the more difficult this becomes to manage. Young people are building larger and larger digital footprints. Those of us who have been online for decades often have to face elements of our past that we might not otherwise have to confront (I’m looking at you, suggestive tumblr gifs!). And on many platforms, other people have access to traces of you that no longer match who you are or who you’re choosing to be online.

It isn’t just performing an articulated identity within collapsed contexts that makes authenticity difficult; it’s also social media’s inability to move on when you’ve grown past a certain point.

Content Collapse

The rabbit hole gets deeper.

This is a further expansion of context collapse, but it’s also sort of an argument against it. Nicholas Carr says that context collapse isn’t the real story of social media anymore, for two reasons.

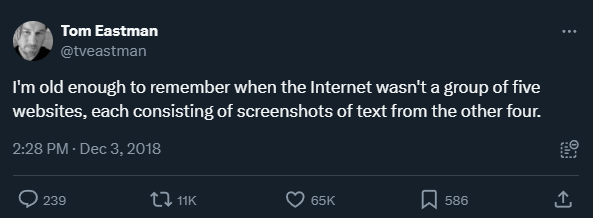

First, people have largely started moving away from sharing personal content in favor of aggregating or curating other people’s posts — news stories, photos, tweets, etc. This has been happening for a while:

The second reason is that a lot of people are abandoning highly public platforms all together. I’ve written about the cozy web before, which is essentially what Carr is referring to. Instead of sharing personal updates with all of our Facebook friends or Instagram followers, many of us are sharing these things in private servers, group chats, or other gatekept communities that insulate us from a lot of the issues that come with context collapse.

As a result — or, perhaps, as a natural plot point within the story of The Algorithm — content collapse has become the more pressing issue, the more “consequential legacy” of social media.

Content collapse refers to the flattening of different types and categories of information. Personal posts, news, entertainment, art, education, marketing, opinion pieces, ragebait are all treated as the same type of information, and we have to respond to all of it using the same set of limited tools.

This reminded me of a January Garbage Day issue (one of my fave newsletters for internet / tech culture) discussing the collapse of broader media apparatuses:

Back in 2018, even with Trump in the White House, we still had a hybrid media environment where still-somewhat-healthy digital publishers, still-somewhat-searchable social networks, and fairly-large national news organizations all competed inside the attention economy…. if something inside of one of those pipelines diverged too much from the others, you could tell simply by consulting the others. Now that this information apparatus, as Tani concludes, is collapsing, you can’t figure out what’s important because, in a sense, nothing is.

Everything is trivialized, we don’t have effective reference points to determine the legitimacy of information we come across, everything in our feeds is now in direct competition, and this consolidates “power over information, and conversation, into the hands of the small number of companies that own the platforms and write the algorithms” (Carr).

Social media collapses ourselves into a single curated performance, collapses time so that all iterations of this identity exist at once, and collapses content so that everything we share is largely indistinguishable from everything else being shared.

The Online Authenticity Paradox

I want to pause to clarify why I keep referring to “social media” instead of something like your website or larger online presence. I’m not thinking of social media as a collection of platforms, but a collection of functions: the ability to easily share, consume, and engage with digital content.

In this way, something like your blog or this newsletter — which people can share and comment on — are forms of “social media”, too. We are all impacted by these strange, boxed-in rules of interacting online, even if we choose to limit the time we spend on the Big Platforms.

And so even our own spaces are susceptible to things like the Online Authenticity Paradox.

This actually started as a business concept. In that context, the “authenticity paradox” describes how prioritizing alignment with your “true self” can limit flexibility and growth. You may not rise to new, interesting, valuable challenges because you are too rigid in how you filter things through your lens of existing identity.

I see what they’re saying. I’ve been in situations to potentially earn more money or grow more rapidly in my career that didn’t feel right “for me”. I don’t think that answer is good or bad, just that it does present an interesting challenge when today’s “self” makes a decision for all of your future “selves”.

Anyway, the Online Authenticity Paradox comes from a small 2021 study where researches tried to gauge people’s perspectives and efforts around being authentic online.

What they found was that, first, authenticity is highly subjective. Some people see it as a deep, intrinsic need that we strive for; some people see it as an artificial performance. But one of the most common definitions participants gave involved sharing both “positive and negative content online”. One participant explained:

to really present yourself authentically, you’d have to document every single thing that’s going on in your life... the exciting parts, the really sad parts and the day-to-day things too. Just like, if you’re going to get food, or if you’re like cleaning up around the house...

I actually disagree with this — that honesty has to assume an air of negativity. I suppose that, to reflect reality, you have to reflect the hardships that come with it. But it’s strange that we apply the same rule to reflecting ourselves, who we are.

But that’s part of the point of the paradox — that something one person sees as deeply authentic might be read as…. not that by someone else on the same platform.

In fact, this fear is what drives the Online Authenticity Paradox. Despite this being the most popular definition, and despite participants’ desire to be authentic, they very rarely shared negative or complex feelings and life events. This is especially true for experiences that might be stigmatized, and for people whose identities are marginalized.

There’s a base level of social judgement that we have to navigate when trying to be “authentic” that, to me and these researchers at least, makes it unachievable for most of us.

This is the paradox: Feeling pressure to share these different parts of your life, but feeling pressure in the opposite direction to keep the more difficult elements to yourself.

Earnestness is a lower-pressure approach to self-presentation.

If authenticity isn’t an achievable “goal” for our online presence, what’s the alternative? Where do we go from here?

One of the reasons I started thinking about this was the discomfort I felt after sending my last newsletter. I’ve been vocal about how important it is to me to explore my full self in digital spaces. How much I value being able to communicate who I am better, more completely, more publicly using digital tools.

So why did I feel so weird talking about how difficult of a time I was having? Why was I so worried about the rules I was possibly breaking?

The answer is a little complex, but I think it comes down to that same fear of judgement and stigmatization that the Paradox study folks were pointing to.

I want to share these things because they’re important to me, and I want other people to know that they’re important to me. We all want to be seen, etc. But there is also value in discernment. In being cautious and intentional about the digital traces of yourself dropped like breadcrumbs on this long walk through the incorporeal digital universe.

That’s not to say that I regret writing or sharing about what’s happening, but that I think it came from a place of trying to be “authentic” — which, as we’ve seen, isn’t totally helpful. And so, in many ways, it felt inauthentic.

Earnestness, in my opinion, is a much more useful and tangible goal.

Authenticity asks us to be real, true to our nature, faithful to ourselves — whatever literally any of that means!!!

But earnestness is quieter, more grounded. All it asks is that we mean what we say. That we feel and act sincerely. To have serious intention and purpose behind our words and behavior. I think that is what we should be aiming for — to have real meaning behind what we’re doing, regardless of whether that is a complete or “authentic” representation of who we are.

You can perform authenticity by making the right posts, sharing the right content. You can create the vibe of authenticity so well that you believe it yourself. Believe this representation of you is true and real and complete.

I don’t think earnestness works the same way. It’s not as tricky. There aren’t any mind-games. You know whether your words are serious, and it’s easier to signal that seriousness to others with your behavior, as opposed to this, like, ideal of self that is constantly changing shape.

But what do you think?

Do you understand where I’m going with this, or do you think I’m making a distinction without a difference? Drop a comment or hit reply if you feel up to it.

I don’t necessarily have a “how” or “what” here. I don’t know what the “process” of earnestness looks like. But I think it’s worth exploring. I think there’s something really helpful about the simplicity of truth over performance. Having a more grounded and consistent reality for your words.

I’ll be thinking about it more.

Cheers,

Victoria

P.S. How are y'all holding up with this weather?? It's currently 97°F here with a heat index of 103°F. No thank-you 🥵

🎧 Singing The Beaches in my head.

💭 Thinking about this weird Horse browser?? Need to do more research, but I'm v v interested 👀

🪩 Wanting to share this article from Tara McMullin, which I have been mulling over for weeks. Social media engagement as reproductive labor?!! 🤯

Member discussion